Eva Hakansson became the fastest woman motorcycle rider on Earth at 434 km/h in 2014, on an electric motorcycle she built herself in her backyard garage. She has since then lost that record to Valerie Thompson, but is determined to take it back. Eva relocated from the mile high city of Denver, Colorado, USA, to Auckland, New Zealand at the bottom of the planet in 2017. A job at the University of Auckland was the motivation for the move, where Eva was teaching CAD, drawing, and engineering design to a total of 2,000 first year engineering students during 2018 and 2019. Her contract ran out at the end of 2019, and Eva decided to move on. Still in New Zealand, her goal was to focus on racing in 2020, and then the pandemic hit… In a change of plans while the pandemic is passing, Eva and her husband Bill switched to another passionate topic – 3D printing and recycling. They founded KiwiFil in 2020, which is now New Zealand’s largest manufacturer of 3D printing filament (basically the “ink” for your 3D printer). Being tree-huggers at heart, the filament is of course made from bio-plastic and recycled plastic.

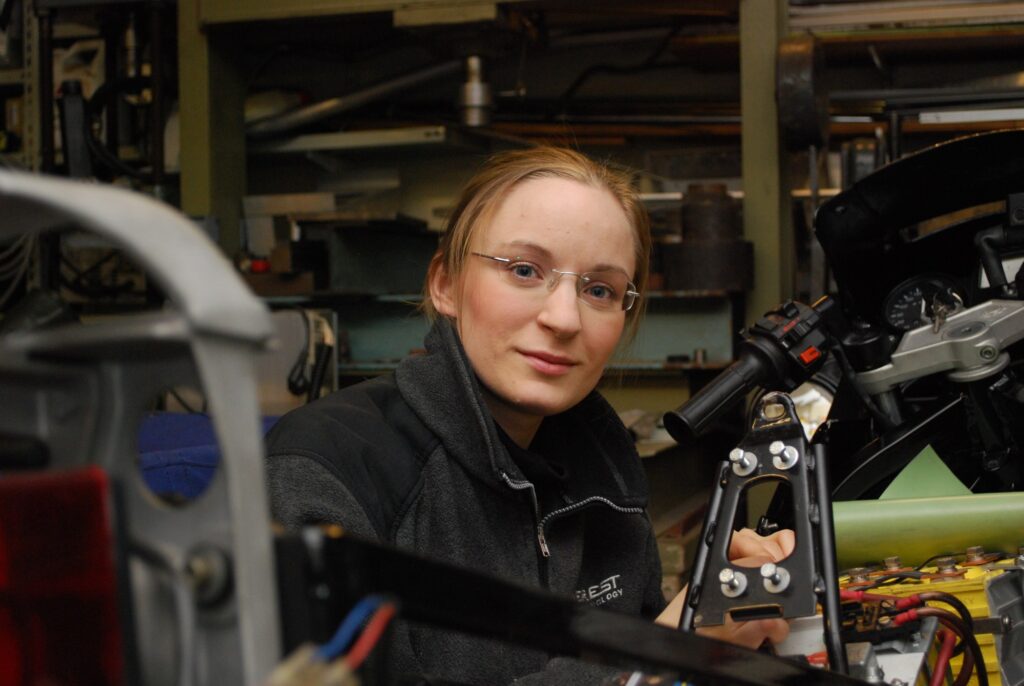

However, back to the topic of racing. If you think this girl is chasing the adrenaline kick from flying across the legendary Bonneville Salt Flats and the Australian counterpart – Lake Gairdner Salt Flats, think again. Eva is a hardcore mechanical engineer and sees the record run itself “about as pleasant as taking a final exam”. Her element is in the workshop, and she feels that welding is a superhero power. Her mission is to show that eco-friendly is far from boring. She readily admits that her racing is really just “eco-activism in disguise”. With the same dedication as a Greenpeace activist, she uses the unusual channel of high speed racing to open people’s eyes and minds for sustainable technology. She also wants to inspire kids to study STEM and to build amazing things with their hands.

Building and racing the KillaJoule and electric motorcycle and its successor “Green Envy” just a very expensive hobby. The Green Envy was finished in February 2020, after a record-fast build of 6 months and 22 days from the first steel tubes were cut until it was loaded into the sea container bound for Australia. The planned debut was March 2020, and Eva and Bill were already in Australia when the world came to a screeching halt. As the world started to close down, the salt flats event was cancelled. Green Envy’s debut was postponed to 2021, but pandemic COVID restrictions prevented Eva to make it to Australia on time for the event. It wasn’t even a third time lucky, because in March 2022, the Australia salt flats were flooded (!) and the event was cancelled again. She is hoping that Bonneville in August 2022 will be the place for the debut, so fingers crossed that the universe is on her side, and she can get a bit closer to the ultimate goal of Green Envy becoming the world’s fastest motorcycle. Period.(If it is well passed September 2022 and Eva has forgotten to update this page – let us know.)

Eva calls her 270 mph (434 km/h) motorcycle “eco-activism in disguise”

Eva Hakansson with the now retired KillaJoule (top) and the brand new Green Envy (bottom).

BEHIND THE VISOR – EVERYTHING YOU WANT TO KNOW ABOUT EVA, BUT WERE TOO POLITE TO ASK:

Born: 1981

Height: 5 ft 2 inches (158 cm)

Nationality: Swedish and US. Lived in Denver, Colorado 2008-2017, and now living in Auckland, New Zealand (which is as far as I possibly can get from my hometown of Nynäshamn, Sweden).

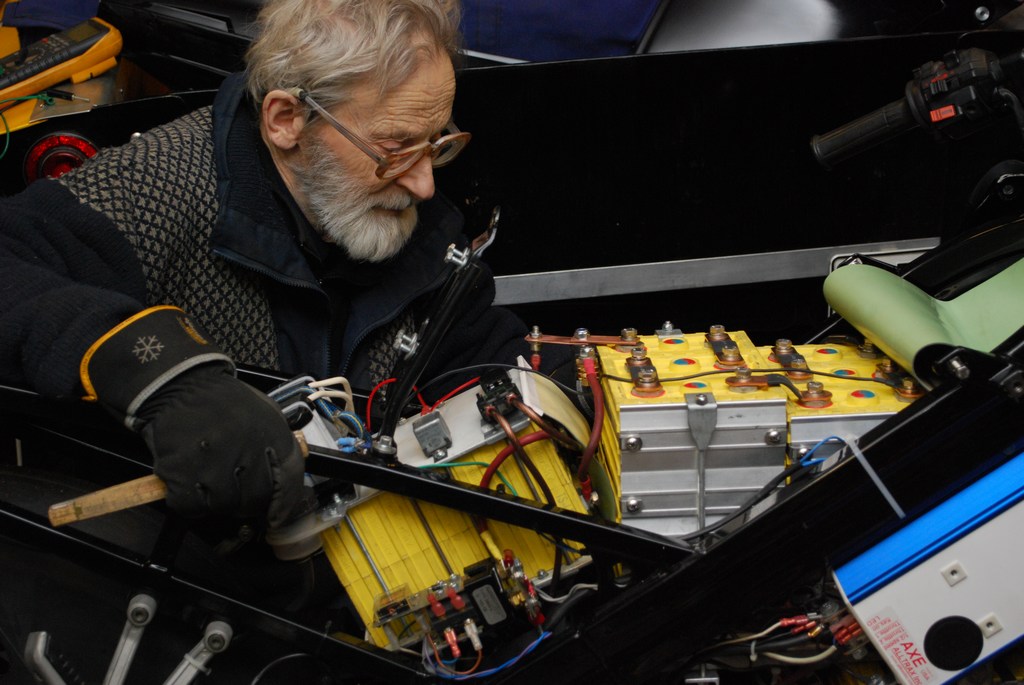

Family: My husband is Bill Dube’, retired research engineer that used to work at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. My parents Lena and Sven and my two older brothers Tomas and Lennart still live in my hometown in Sweden. Did I mention that all of us have engineering degrees, including my mother?

Eye color: Blue

Hair color: My husband Bill says that my hair is “champagne blonde”. I say “rat color”. He then rolls his eyes and sighs.

Favorite dish: Something I don’t have to cook, I rather spend my time in the garage than the kitchen. However, if I had to eat one thing for the rest of my life, it would be salads. I absolutely love salads.

Favorite song: I listen to both kinds of music – country and western! The KillaJoule is built to the sound of country and western on the radio. It was built in the wild west, after all. Among the country artists, John Denver and Ken Dravis are my absolute favorites. Which both happen to be from Colorado.

Although not country, as for specific musical performances, Beyoncé’s “I was here” at the UN’s headquarter at World Humanitarian Day 2012 is unbeatable!

Education: I have almost more degrees than a thermometer! 😉 Bachelor degree in Business Administration (Mälardalen University, Sweden, 2005), Bachelor degree in Environmental Sciences (Mälardalen University, Sweden, 2005), Master degree in Mechanical Engineering (University of Denver, CO, USA, 2013), and a PhD in Mechanical Engineering (University of Denver, CO, USA, 2016).

Why did you build the KillaJoule and the Green Envy? I call KillaJoule and Green Envy “eco-activism in disguise”. My mission is to show that eco-friendly can be fast and fun, and hopefully make people that otherwise wouldn’t be interested in low-emission vehicles be aware of their potential. Speed is a great way of showing the potential of battery power, because fast is always in fashion! Another purpose of the KillaJoule is also to show that women can be excellent engineers, and to encourage girls and women a career in science and technology. Also, I have to admit, that setting world records in a vehicle you built with your own hands and that you ride is really satisfying.

Day job: I came to New Zealand because I got a job as a lecturer in mechanical engineering at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. I had planned to take 2020 as an unofficial “sabbatical” year to focus on racing. However, as we all know, that’s the year when the world came to a screeching halt. I had already quit my job at the university, and in a change of plans while the pandemic is passing, my husband Bill and I switched to another passionate topic – 3D printing and recycling. We founded “KiwiFil” in 2020, which is now New Zealand’s largest manufacturer of 3D printing filament (basically the “ink” for your 3D printer). Being treehuggers at heart, the filament is of course made from bioplastic and recycled plastic. I am hoping that KiwiFil will be successful enough that I don’t have to go back to regular employment. I don’t mind working around the clock in my own business, but 9-5 has never really suited me well.

Fast is always in fashion!

Did you really build the KillaJoule yourself? About 80 % of the hours, blood, sweat, and tears that went into the KillaJoule are mine. The rest is built by family and friends. There is always a team behind every successful racing vehicle, you cannot do everything yourself. The motorcycle is built from scratch in my two-car garage behind my house.

How about the Green Envy? Did you build that one too? The Green Envy is much more of a team work. We have amazing supporters and volunteers here in New Zealand. The most important has been Mulcahy Engineering and Axis Industrial. Mulcahy supported with all laser cutting and plenty of material. Peter Hopperus and Quintin Shamrock at Axis Industrial then welded up the main portion of the frame as well as the front and rear suspension. When that was done, we brought it home and Bill and I built basically the rest of the vehicle. In addition to Peter and Quintin, Tom Parker, Steve Lovell, Martin Powditch, Matt Pearce, Juan Robertson, Summer Xia, Isaac Grigor, Blake Roberts, Richard Micheel, and Graham Sparey-Taylor have helped with the build. The on-track crew also includes Kel Grayson, Amy Elliott, Sam Elliott, Tom Bishop, Debbie Robertson, Howard Ludgate, and Frank John.

How does it feel to set a new record? I wish I could say that it is a big rush, but it isn’t really. The closest I can describe it as a 2 minute long mix of horror, boredom, and magic. Setting a new record means that I am going faster than I ever have gone before, and that the bike is going faster than it ever has. Accelerating up to a speed where I have been before is typically so uneventful that it is almost boring, but as soon as you surpass that speed you are entering uncharted territory. It is known that stability problems can occur very suddenly, so it is quite nerve-wrecking. The vehicle is also extremely tight and claustrophobic. To be honest, that alone took a while to get used to. The relentless desert sun beating down doesn’t make it any more pleasant. But, at the same time, the feeling when everything works flawlessly is like magic. Years of work finally pays off, and it is like time stops. When I have finished a run, all my nervousness and discomfort quickly vanishes and is replaced by a huge grin. I say, “Well, that was easy, let’s do it again”.

How long is the track and how long does the run take? From 2010 through 2017, we ran all the the record attempts at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, USA. Since, 2019, our “home” venue is Lake Gairdner Salt Flats, Australia. It is a dry salt lake that t is perfectly flat and looks like a snow covered lake. The track is perfectly straight and it is consists of salt that is groomed and prepared to make a very smooth surface. I typically has about 4 miles to get up to speed, 1 mile where my speed is measured, and 4 miles to slow down. It takes me 1 to 2 minutes to get up to speed, and it takes about 13 seconds for me to cover the measured mile. When I exit the measured mile, I release my brake parachute and roll to a stop. In order to set a record, you have to repeat the speed with a record backup run. If the average speed of the two runs exceeds the previous record, I will have a new record.

Best racing memory: Setting my first world speed record the day I turned 30. It wasn’t particularly impressive at 138 mph (222 km/h), but it was my first international record. Hitting 200 mph was as exciting as you would think it would be, maybe even more exciting. And of course all the wonderful people racing at Bonneville Salt Flats as well as Lake Gairdner, they are all like a family that you meet once a year. There is very little cut-throat competition, we are all in a salt desert far from everything and we all help each other set records and go faster.

Worst racing memory: There are so many that I don’t even want to think about it…. It is definitely not a glamorous life… Perhaps the day we had to replace five (5!) flat tires on the race trailer, or maybe the time we blew a head gasket on our hauler truck, and it water-locked, and wouldn’t start, miles from the pavement, on the salt, in the rain!

Why land speed racing? It is incredibly safe compared to other kinds of world class level racing (there are no other competitors on the track, and there is nothing to hit). Land speed racing is the last fully unlimited racing where innovative engineering is encouraged. Most regular racing is so regulated that there is no room for innovation. Also, speed records are so tangible and easy to communicate, everybody can relate to speed. When you set a new record, you don’t just beat the other competitors at the same event, you beat everybody in the entire history! That’s cool!

What motivates you to set new records? I have an inner force that drives me to do things that nobody else has done before. I get an incredible joy from pushing the boundaries of engineering and pushing my own capabilities. I enjoy being the best in whatever I do, but the journey is actually more important than the goal. It may sound like a cliché, but it needs to be that way because your goal is always a moving target. There is always somebody else that is faster. You better enjoy the journey, because the journey is life-long.

How do you prepare for a race? Even if I need to be quite fit for the job, my motorcycle is the real athlete. It requires “care and feeding” just like a race horse or airplane. Everything is pushed to its limits during a record attempt, so all the parts have to be in top notch condition. With a very short racing season – the salt flats are only dry in August and September every year – the preparations for next year’s record attempt begin the day after you come back from the race. Corrosive salt gets in everywhere and has to be cleaned out, a process that can take every evening for a month. Things that are broken have to be fixed. There are always parts that need to be painted, any little scratch in the paint on the frame and the steel starts to rust. All electrical systems have to be checked, onboard fire extinguisher system has to be serviced, flame suit has to be washed and checked, and a gazillion other things. The goal is always to go faster, which means that the winter, spring, and early summer is being used for upgrades. One winter we built a new battery pack with higher power, a job that took several months. Another year we upgraded to tires that can be used for 300+ mph, that job took all winter. This year we improved the aerodynamic outer aluminum skin on the sidecar, which took all spring. We used to only work evenings and weekends, which meant we were busy all year around. In 2020, we have quite a bit more time, but also a whole lot bigger goals! The Green Envy is built for 400 mph (650 km/h) with the goal of becoming the fastest motorcycle in the world. Period.

Biggest challenge in your racing effort? Budget! Budget! Budget! As serious as my world records are and as slick as my on-line appearance may make it seem, my husband Bill and I are very much a garage team. Just Bill and myself working on the bike in a rented warehouse unit. Friends pitch in now and then, but we do the vast majority of the work. We have sponsors for some of the main components such as the battery and motor, but most other costs are paid out of pocket. We have to be very innovative to keep the cost down to a level we can afford. Short on money means you have to be long on clever.

Is the KillaJoule really just a hobby? Yes, it is a really expensive hobby. I wouldn’t say that it is “just” a hobby, it has consumed all my spare time since 2010 years. I used to be a lecturer in mechanical engineering at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, but my contract ran out at the end of 2019 and I decided to move on. Bill just retired from his position as research engineer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). I took 2020 off to focus on racing. However, racing has been cancelled due to the pandemic so Bill and I are working on an exciting project to turn recycled plastics into 3D printing filament.

Biggest asset? Determination! I am a quite impatient person, but I am tenacious. To be the best in anything, you have to work on it every day. You need to want it so badly, that you never give up. I also enjoy the building process more than riding, which is important because you spend 360 days of building for 5 days of racing… Bill describes me as a Border Collie. If I am not constantly activated and stimulated, I start to chew on the furniture.

Most important skill? Project management! There is a very important saying in racing: “To finish first, one must first finish.” If you are not ready when the race starts, you will not win. A race is a firm deadline, and it takes serious management skills and discipline to get everything done in time. My favorite saying is “Whatever I do today, I don’t have to do tomorrow”. That’s how I get so much done.

“To finish first, one must first finish.”

What’s the secret to the KillaJoule’s insane speed? Clever engineering and optimization! Working on a shoestring budget, you have to do the math and spend your resources wisely. If you do that, you can set world record as a backyard team.

How much has the KillaJoule cost? I decided early in the project to never count exactly how much it has cost, but I know that our monthly credit card bills many times have had the same size as the pay check. We are somewhere between $100,000 to $150,000 out of pocket, and our sponsors have put in a similar amount in parts and labor. A lot of the cost is for the support equipment such as trailer, truck, generator, tools etc. We could have paid off our mortgage early if we hadn’t built the KillaJoule, but that wouldn’t have been nearly as much fun. 😉

What about the Green Envy? The Green Envy is about $250,000 in parts, and probably $500,000 in labor if you were to pay full retail price. I will build you a copy for $1,000,000. 😉 The Green Envy has re-used all the support equipment from the KillaJoule, as well as other parts of the powertrain.

It is OK to be laid-back, but you can’t be lazy if you want to be the fastest in the world.

“Whatever I do today, I don’t have to do tomorrow.”

EVA’S STORY – FROM ZERO TO THE WORLD’S FASTEST ON A SHOESTRING BUDGET

It’s in the genes!

I was born in Sweden in 1981. Both my parents are mechanical engineers, and both my brothers are electrical engineers. I was the last one in the family to earn my engineering degree. Just like me, my dad built and raced motorcycles in evenings and weekends. My mom was his mechanic. I went to my first race track in the baby carrier, and I have been interested in technology as long as I can remember. I call my passion for engineering and racing “a genetic disorder”. According to my parents, I built a “nuclear power plant” from cans and cardboard in the garage when I was 4. My dad worked as an engineering consultant out of our home, and he had a full machine shop in the basement. It wasn’t until many years later I realized how unusual, and beneficial, it was to know how to machine, weld, and to have other machine shop skills.

Sven Håkansson – Swedish Champion on 50 cc roadracing 1962. He built the motorcycle, including the engine, in evenings and weekends. Photo: Åke Wremp

My mom Lena was my dad’s racing mechanic, and they were for a few years also running a small motorcycle dealership together. The headline in the regional newspaper says “Couple from Hälsingborg has a unique business: She is Sweden’s Miss Motorcycle”.

I call my passion for engineering and racing ‘a genetic disorder’. My dad was a racer, and everybody in my family – even my mom – is an engineer.

From the age of 10 through 16, I sidetracked from the technology a bit and spent my spare time taking care of competition horses (Three Day Eventing horses, to be exact, meaning that the same horse would do dressage, cross-country and show jumping during the same event). While thoroughbreds are amazing and beautiful animals, I was more interested in the horse equipment than the horses themselves. I repaired everything from saddles to rugs, and improved or invented new equipment where needed. When the couple I worked for moved from town, I felt that I was done with horses.

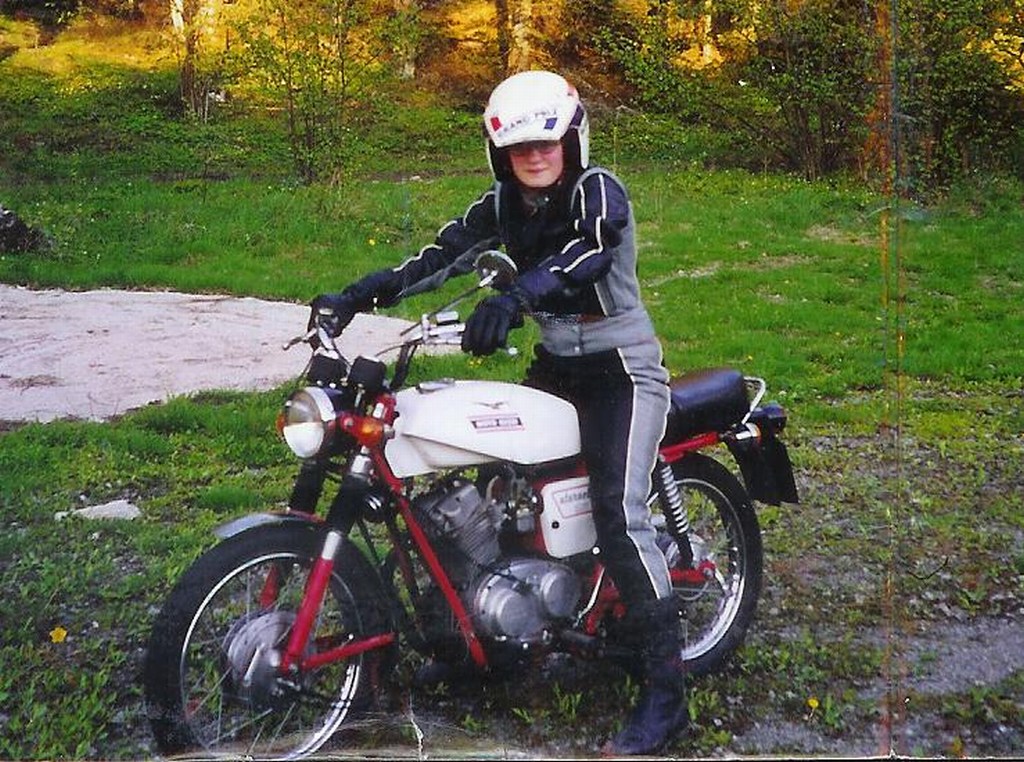

When I turned 16 – the legal age to drive a lightweight motorcycle in Sweden – I traded the horses for my first motorcycle. The 125 cc Moto Guzzi Stornello from 1972 was bought as a pile of pieces. I helped my dad put it together, and it started on the first kick after having been in pieces for 18 years! At 18, I got my first car: a quite abused Saab 900 Turbo that had belonged to my brothers. The first thing I had to do was to replace the broken gearbox (transmission). The car had been leaking oil for several years, so it was a quite messy operation. I got the job done under the supervision of my dad, and I certainly earned the respect from the teenage boys in my neighborhood. Although I would prefer to never change a gearbox again, it did indeed give me a real taste of technology and boost in self-esteem.

My first motorcycle – a 125 cc Moto Guzzi Stornello from 1972.

A growing passion

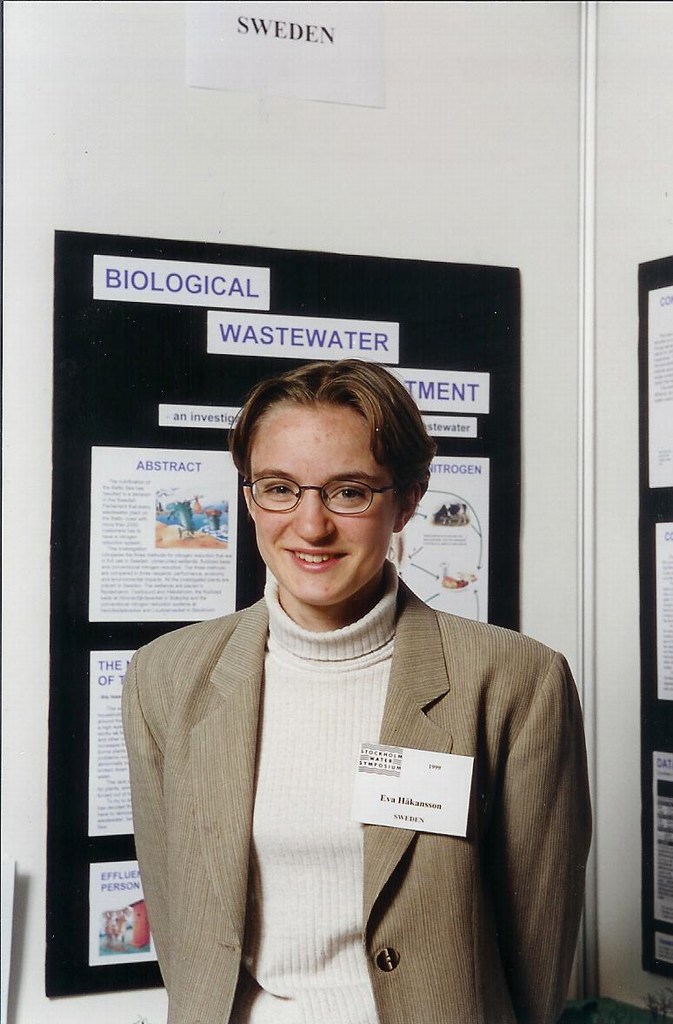

After finishing high school with concentration in natural science and technology, winning several first-places in the national science competitions with “clean technology” projects (which also, of course, included building things), working a year as a lab assistant at an oil company, working half a year at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and another half a year at the oil service company Schlumberger in Cambridge, UK, it was time for college. I decided to broaden my mind and picked an unexpected field of study. Because money rules the world, I decided to get a business degree. I earned two degrees at Mälardalen University: a bachelor in business administration with emphasis in ecological economics, and then a bachelor degree in environmental sciences. I also took classes in energy technology, wind power, fuel cells, and nuclear power. In hindsight, it would have perhaps have made more sense to get an engineering degree, but the business degree has come in handy many times. I wrote my bachelor’s thesis about political incentives for introduction of low emission cars. The intricate relations between technology, economics, and the environment, fueled my interest for low emission cars. An interest that soon grew into a passion for electric drive.

Winner of the Swedish Junior Water Prize (Svenska Juniorvattenpriset) 1999 and Swedish representative in the international science competition Stockholm Junior Water Prize. Right: With my dad Sven.

Winner of the Swedish Junior Water Prize for the second time in 2000, and again representing Sweden in the Stockholm Junior Water Prize. Right: Receiving my certificate of participation from the Swedish Crown Princess Victoria. As a frugal Swede, I had sewn the gown myself. It was both cheaper and more fun.

My passion for electric drive comes from its characteristics. An electric vehicle is like chocolate without calories: it gives me everything I want – power, speed, and torque, without the things I don’t want – pollution and noise. I know that engine sound isn’t considered a “noise” by many people, but the feeling of power and speed is actually much more intense in complete silence.

With newly found passion for electric vehicles but without a clear vision about my future, I moved back in with my parents and spent most of my time writing about electric vehicles for little or no pay. I wanted to move out of my parents house and applied for a trainee job located on the other side of the country, hoping to get to work with corporate sustainability. I made it through intelligence tests and interviews, but lost to the other candidate at the last round because I was “too intelligent” (this was the recruiter’s actual words, I had scored highest on the intelligence tests of the several hundred applicants). The recruiter questioned why I got a business degree and applied for a trainee job focused on sales when I clearly was more suitable for a career in research and engineering. I didn’t get the job which was a disappointment, but it made me start thinking about changing path is life. Little did I know that my life would change a whole lot in a near future, and that the real adventure had far from started.

2007 was going to be a year that changed my life. Although still living off my parents and savings, I was involved in several exciting projects. My dad had built an electric roadster (an open sports car), and I really wanted my own electric car as well. However, I had neither the garage space nor the budget for a car. My dad agreed to help me convert a motorcycle to electric drive; a project that would fit both the garage space and my wallet. The work took all of 2007, and the result became Sweden’s first street legal motorcycle – the “ElectroCat”. Based on a Cagiva Freccia C12R-90, an 125 cc Italian two-stroke motorcycle, the electric version has equivalent performance to the original combustion engine motorcycle. The ElectroCat passed the registration inspection and became a street legal vehicle in Sweden in January 2008.

Making the last adjustments on the “ElectroCat” the night before the final inspection to become a street legal motorcycle. January 2008

Me and ElectroCat.

Electric racing is like chocolate without calories: it gives me everything I want – power, speed, and torque, without the things I don’t want – pollution and noise.

The ElectroCat was just the beginning of the adventure that was to come. In the spring of 2008 I was invited as a guest speaker to the Swedish Parliament to talk about the advantages of electric cars. ElectroCat was invited too, and it was most likely the first time a motorcycle had been _inside_ the parliament building. The Secret Service was a bit skeptical until they learned that there was no fuel in it. Luckily the bike just fit in the elevator. We brought it in the night before through a back door, and I felt that I was in the middle of a James Bond movie.

Eva and ElectroCat inside the Swedish Parliament building with Eliza Roszkowska Öberg, member of the parliament and the person that kindly invited me to hold a presentation.

A life-changing picture

2008 was also the year when I published my first book, a popular scientific book about hybrid and electric cars “Hybridbilen – framtiden är redan här!” (The Hybrid car – the Future is already here!). It was never a best seller, but I am still proud of my accomplishment. I learned the insane amount of work it is to write a book. I was correct in my predictions that hybrid and electrics are the future – every major car manufacturer either already sells hybrids and electrics, or they are in the pipeline for release in the near future.

“The hybrid car – the future is already here!”

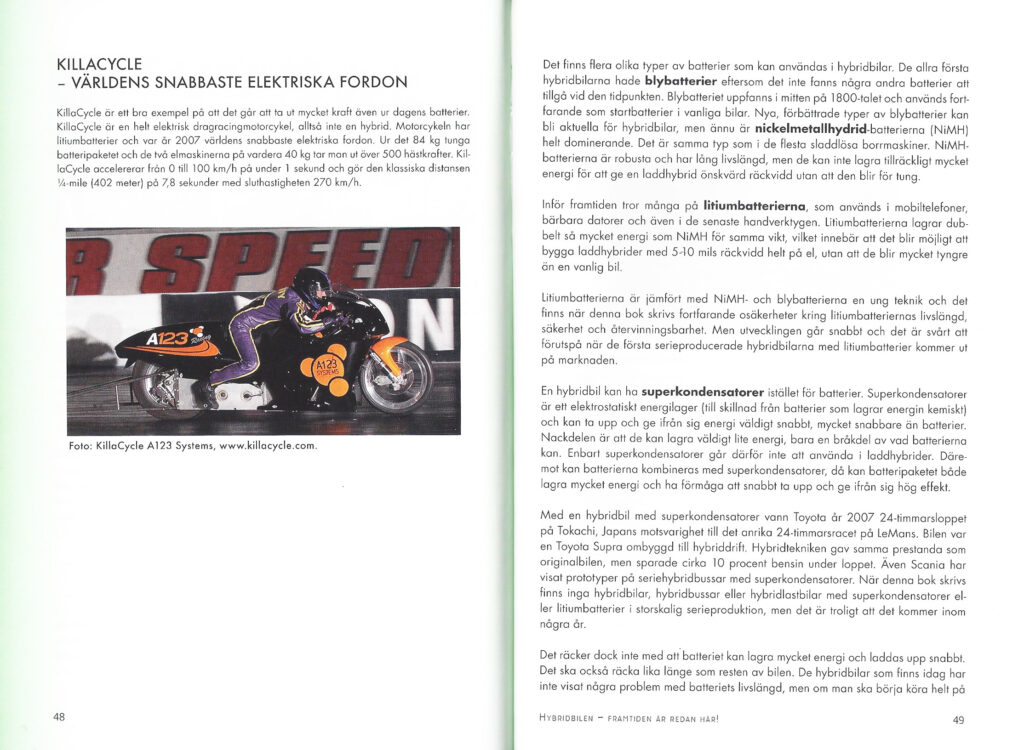

While publishing my first book and speaking in the Parliament were way cool experiences, my most life-changing encounter had already happened in late 2007. It all started with that little book about electric and hybrid vehicles. I had heard about the world’s quickest electric vehicle – the KillaCycle dragracing motorcycle, and I wanted to use a picture of it in my book. I tracked down its owner Bill Dube’ online and asked for permission to use his photo. Bill replied with a several page long email about the bike. We kept in email contact, and it turned out that we were planning to attend the same electric vehicle symposium in Los Angeles in December 2007, the EVS 23.

The picture that changed my life.

It perhaps wasn’t love at first sight, but it was certainly love at first conversation. Despite a large age difference, Bill and clicked directly. We were soul mates! I commuted back and forth to Colorado on “tourist visa” during 2008, but this was not a sustainable solution. Being an engineer and a professional problem solver, Bill came up with the solution: Get enrolled in engineering school and apply for a student visa! I thought, “Why not?”. I did regret that I had chosen to pursue a business degree instead of an engineering degree, and here was my chance to change that. I jumped head first into engineering school, which was going to be a big challenge. First off, I hadn’t studied advanced math and science for over 10 years. Secondly, I was doing it in a foreign language. Nevertheless, I made it as almost a straight “A” student; a B+ in chemistry made a dent in my graduate GPA to 3.97 from 4.0, but I feel that I have no right to complain. Many people would give their right hand for that GPA. I graduated with a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from University of Denver in 2013, and with a PhD in the same field in 2016.

Two geeks in love

The student visa was a quick immigration solution, and pursuing an engineering degree made my parents slightly less unhappy about my emigration to the USA, but it was not a long term solution. The obvious solution was to get married. Although Bill and I are romantics, we would not got married so soon if it did not have practical advantages. The summer of 2009 we were pronounced “Anode and Cathode, may the sparks fly!” as we exchanged non-conductive ceramic wedding bands. The “chapel” was a prototype electric delivery truck, and I had ridden down the aisle on the ElectroCat while Bill entered on an electric bicycle. I wore a traditional Swedish costume, of which parts had belonged to my grandmother and parts were hand-made by my mom just for me. She had even woven the fabric for the skirt. It was probably the geekiest wedding of the decade, and absolutely perfect!

We were pronounced “Anode and Cathode, may the sparks fly!” as we exchanged non-conductive ceramic wedding bands.

Life as married continued at high speed. We were racing Bill’s dragracing motorcycle the KillaCycle, setting new records in the 1/4 mile, but dragracing is difficult to communicate to the public. It is not the top speed that is important in dragracing, but how quickly you get to the finish line. KillaCycle’s best time ever in the 1/4 mile was 7.6 seconds, which is respectable in dragracing circles, but almost impossible to communicate to the public. “7.6 seconds to what? To 60 mph? That’s not very fast”, was a frequent comment. 7.6 seconds is quick, very quick, because it is equivalent of 0 to 60 mph (96 km/h) in less than one second! Even after explaining that, the follow up question was almost always “But how fast is it?”. KillaCycle’s speed of 174 mph (280 km/h) at the end of the 1/4 mile is also respectable and was, at the time, the fastest ever recorded for an electric vehicle, but it didn’t impress the general public. Bill and I decided that we had to do something else to make people interested in electric vehicles.

Goal: To become the fastest in the world

I decided that I wanted the answer to the question “How fast is it?” to be at least “300 mph” (484 km/h). We didn’t have the budget or garage space for a car, so it had to be a motorcycle. It also had to be a streamliner motorcycle to be able to achieve that kind of speed. A streamliner motorcycle means that you sit inside the vehicle, like in a car, but that it only has two (or three) wheels. After some failed partnerships with other people, we decided to do everything ourselves and finance it out of our own pockets. Never having built a streamliner motorcycle ourselves, we were ridiculously optimistic. We thought it would take about 6 months and a budget of $10,000. It would end up taking 10 times longer and cost us 10 times more…. but it was worth it in the end! The KillaJoule streamliner would bring us joy and adventure that surpassed our wildest imagination.

Anyway, in spring break 2010, we cut the very first steel tubes that would become the chassis for the KillaJoule. We took it to Bonneville in September, but I couldn’t keep the two-wheeled motorcycle upright. We still don’t know if it was a rider problem or a motorcycle problem. However, we found the perfect solution: to turn it into a sidecar motorcycle. We didn’t know that sidecar streamliner motorcycles was a competition class until we saw them at Bonneville. If we had known, we would have built it as a sidecar from the beginning. Nevertheless, we went home and added a sidecar wheel and set our first international record the next year. The third wheel solved the stability problem and I call it “my permanent training wheel”.

It took four days (!) to build the basic chassis with the help from our friends Clay and Gary Gardiner, and four more years (!) to become the fastest electric motorcycle in the world.

2010 – our first year at Bonneville. We didn’t set any records or even made a full run down the track, but we learned that to finish first, one must first finish. Photo: Michael Cooper.

A first taste of the joy of land speed racing. The joy and adventure the “KillaJoule” was going to bring us over the following years would surpass our wildest imagination.

We couldn’t afford a new racing suit for $1,000, so we picked up this 16 year old racing suit for a bargain online. It made me look like the Michelin Man and it was roasting hot inside.

We didn’t have a crew, so Bill and I drove the 12 hours to Bonneville alone, hoping that somebody would help us if we needed it. We ran in to some old friends, and made some new friends, that all pitched in for the pure joy of racing.

To finish first, one must first finish.

2010 was a crazy year. As if it wasn’t enough of a project to build a streamliner, I had just moved from University of Colorado to University of Denver, and the academic challenge was at a level I had never experienced before. I had also made the foolish decision to enter the ElectroCat in the legendary Pike’s Peak International Hill Climb, perhaps one of the most dangerous races in the world. The race starts at 9,400 ft (2,900 m) above sea level and ends at 14,110 ft (4,300 m). It is 12 miles long and has 156 turns. I had assumed that the ElectroCat would be so slow compared to the other motorcycles that I would be OK with my very limited racing experience. That might have been true, but I had misjudged how hard it was to drive back downhill from the mountain.

During the return run from one of the practice sessions, I got the rising morning sun in my eyes and ended up in a sand filled ditch. I probably picked the absolutely best place to run off the road, because crashing at Pike’s Peak typically means falling over the edge of the mountain. Thanks to state-of-the-art personal safety equipment such as helmet, back protector and neck protector, I only broke my wrist, and rode the bike back down to the pits before heading to the emergency room. I joked that the mountain had “slapped me on the wrist” and told me that I had no business in this race. We patched up the bike and it participated in the actual race a few days later with Pike’s Peak veteran John Scollon as the rider. Although finishing far down the list, it was the first electric motorcycle ever to finish the race. However, it wasn’t the first time an electric motorcycle had made it to the summit. Weeks before the race, I drove the ElectroCat up the top of the mountain in order to get data for the energy needed for the race. It turned out that I had done the math exactly correct, plus I also made a little bit of history. 🙂

ElectroCat – the first electric motorcycle to make it to the top of Pike’s Peak, 14,110 ft (4,300 m) above sea level. May 2010.

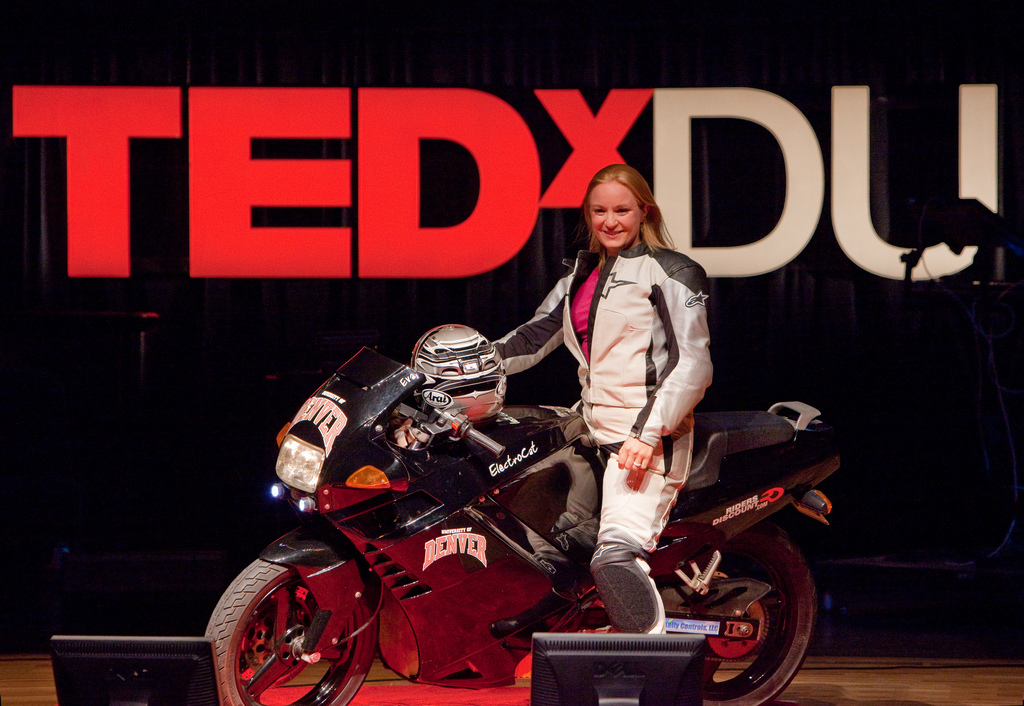

Before I crashed the ElectroCat at Pike’s Peak, it had made an appearance on stage at TEDxDU. It was indeed a crazy year. You can find my TED talk below and on my video page.

If I know myself correctly, the years following the crazy year 2010 were probably the most normal years that Bill and I will ever get. I studied and Bill worked his day job building scientific instruments for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). We pecked away on the KillaJoule on evenings and weekends, adding a sidecar for 2011 and then upgraded the drivetrain from almost stone age DC (direct current) motors to space age AC (alternating current) motors. We had our fair share of problems and we were staying around 200 mph for several years. Things were mostly uneventful and almost boring. I decided that if I hit 250 mph in 2014, it would be my last year in land speed racing. I felt that I didn’t get any further and the enjoyment wasn’t there anymore. I was going to be both right and very wrong about 2014.

Love birds – Bill and Eva. Photo: Barbara Fuentes

Mission accomplished: Zero to the fastest in the world in five years

2014 was another crazy year. My research group at University of Denver, led by Dr. Maciej Kumosa, had just received grant from the National Science Foundation to form a research center for high voltage and high temperature materials, the HVT Center. As one of the more senior graduate students and with lots of experience in PR, I was elected to be the Marketing Director in addition to my role as PhD student and research assistant. The KillaJoule streamliner had been 5 years in the making, and I had not reached the results I wanted. We made a few more upgrades over the winter, including changing to the latest in battery technology from our sponsor A123 Systems.

“KillaJoule” in front of our bio-diesel powered generator for CumminsOnan that gives us green power at the track. The charging at home used to be done with solar in Colorado, which also powered our Nissan Leaf electric car that we use for commuting. Here in New Zealand, we charge with 100 % renewable electricity.

Bill and I at the flooded Bonneville Salt Flats. Heavy rain during the night had made the surface useless for racing, but gives great photos. Photo: Bonneville Stories

We went to Bonneville and slowly ramped up the speed with every run. We set a new record at 240.726 mph (387.411 km/h), the fastest official two-way speed record ever for a female motorcycle rider. We went back to Bonneville two weeks later. After a nice shakedown at about 200 mph, which felt like a walk in the park after going 240 mph just a couple of weeks earlier, I sat down with my spreadsheet. Carefully analyzing the data logged in the bike, the math said that it should theoretically be able to do 265 mph (426 km/h). Typically, a vehicle never goes as fast as you think it will. However, we thought there would be a chance to take the unofficial record for a female rider at 264 mph. This was a single run made by Becci Ellis on a regular sit-on motorcycle at an airport in the UK, quite a brave feat in itself. With a theoretical chance at 265 mph, I turned out on the track deciding to give it everything it had. The speedometer in the bike “only” showed 259 mph, but I knew that it was a bit pessimistic (the front tire grows at speed and offsets the speedometer reading a little bit), but I wasn’t sure how much. When the timing folks reported on the radio that we had run 270.224 mph (434.883 km/h) I knew this wouldn’t be my last year of racing. I was the world’s fastest female motorcycle rider, and 300 mph was simply too close to quit now.

2015 rained out, 2016 and 2017 were kind of “meh” years from a racing perspective although I finally manged to get an official record over 400 km/h (249 mph). 2018 we had to skip because we were moving to New Zealand. 2019 we raced at Lake Gairdner in Australia for the first time. That was a huge adventure and KillaJoule’s last official race. You can read that whole story here.

From a career perspective, 2016 was great because I received my PhD in Mechanical Engineering for the University of Denver, Colorado, USA. A major moment in my life! Bill followed shortly and received a PhD in Physics from University College of Cork, Ireland, in 2018. That was the cherry on the top of the cake for after a long career dedicated to science. It was a big deal for both of us. And I thought I was a late bloomer graduating at the age 35…

With a PhD in mechanical engineering on the resume, a new job as lecturer in mechanical engineering at the University of Auckland, New Zealand and the new streamliner Green Envy on the drawing board, the adventure started for real in 2018. However, 2019 I realized that the University of Auckland wasn’t a good fit for me (I am saving all the details for my memoirs. ;-). My contract ran out at the end of 2019, and I decided to move on. I took 2020 off to focus on racing, then the pandemic happened and all racing was cancelled. Bill and I decided to just coast through the year and see where it will take us. Bill’s modest pension keeps the lights on, and we are working on some quite exciting projects together. One particularly exciting project is to make 3D printing filament from recycled plastics. We aren’t the first to do this, but we are trying to be the most clever. 😀 You can find our business KiwiFil here, where you can also get your very own recycled filament for your 3D printer.

If it isn’t on video, it didn’t happen! With a minimal crew at the track, I have to take care of the video myself. I simply got tired of the crew forgetting to turn on the cameras, and they got tired of me yelling at them. I have two remote controlled GoPro cameras: one in the driver’s compartment and one on the outside. In addition to running through the procedure to start the bike, that includes about 10 different switches that have to be turned on in the correct order, I also start the cameras. A recent addition is also a 360 camera supplied by our sponsor Parts Giant. You can see 360 degree footage from Australia in 2019 below, and take the KillaJoule for a ride at 236 mph (380 km/h).

If it isn’t on video, it didn’t happen! With a minimal crew at the track, I have to take care of the video myself. I simply got tired of the crew forgetting to turn on the cameras, and they got tired of me yelling at them. I have two remote controlled GoPro cameras: one in the driver’s compartment and one on the outside. In addition to running through the procedure to start the bike, that includes about 10 different switches that have to be turned on in the correct order, I also start the cameras. A recent addition is also a 360 camera supplied by our sponsor Parts Giant. You can see 360 degree footage from Australia in 2019 below, and take the KillaJoule for a ride at 236 mph (380 km/h).

The photo that almost made my Facebook page blow up. It was a spontaneous photo. A friend and fan had brought the dress because she wanted a Marilyn Monroe inspired photo of me. We didn’t have any suitable shoes, so I decided to simply be barefoot. Standing on the bike was also spontaneous. I had never done it before, but I knew the construction would be strong enough to carry my weight (I built it, so I know where I can stand on it without damaging it.) If you look carefully, you can see that I have a terrible farmer’s tan and that I am wearing the yellow rider’s wristband. I was thinking of removing it in Photoshop, but I thought, “Why should I be embarrassed over my farmer’s tan? It just shows that I have worked on an important project all summer instead of lying at the pool”.

I tried to reproduce the famous KillaJoule photo with the Green Envy. Because we didn’t make it to the salt in 2020 (racing was cancelled due to the pandemic), this photo was taken in an industrial backyard and the background was replaced with the Lake Gairdner. 2021 we missed racing Australia again due to pandemic travel restrictions, and 2022 the salt desert flooded (!). We are hoping to get to Bonneville in 2022 (and I hope I will remember to update this page when we know how it went (if I have forgotten to update it, please let me know)).

Follow the new adventure with the Green Envy on GreenEnvyRacing.com and on Facebook (you don’t have to be a Facebook member, just ignore the annoying prompt to log in) as well as on instagram.

Cover photo by Kevin Smith, Top Dead Center Photography.

Did you find a mistake on this website? Or information that is outdated? Please let me know! It is hard work to keep websites updated, and I appreciate if you tell me when something doesn’t look right. Thank you! // Eva